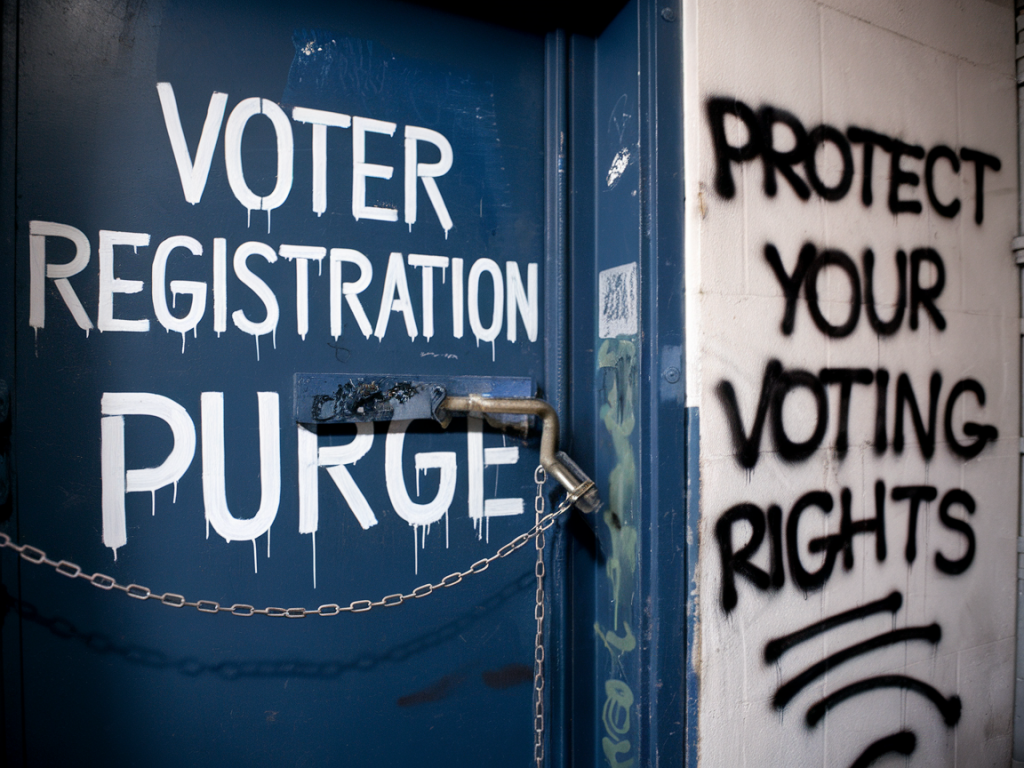

I remember the first time I learned about voter registration purges. It wasn't in a courtroom or a policy brief; it was at a kitchen table with a neighbor who'd received notice that her registration was cancelled because mail to her address was returned. She'd voted in every local election for years. The notice didn't explain how a habitual voter suddenly ceased to be one. That moment stayed with me: the idea that a single administrative glitch could interrupt someone's civic life felt both shocking and, increasingly, normal.

Why purges keep happening

There are several reasons voter registration purges persist across the United States and in other democracies. Some are administrative: election offices rely on imperfect data sources and outdated processes. Some are legal: state laws and federal statutes create frameworks that, intentionally or not, encourage removal of registrants under certain conditions. And some are political: decisions about how aggressively to maintain rolls can reflect partisan calculations about who benefits from deeper or shallower registration lists.

Operationally, many jurisdictions clean voter rolls using lists from the postal service, driver's license offices, or databases that track deaths and criminal convictions. Those data sources can be noisy. Mail can be returned for people who are temporarily away, traveling, or living in a location that doesn't match official records. People might move within a county but still be eligible to vote at their new address. Errors compound when different systems don't talk to each other or when staff are under-resourced.

On the legal side, the National Voter Registration Act (NVRA) of 1993 requires states to remove voters who are no longer eligible, but it also prohibits removal solely for failure to vote. Interpreting and implementing that law has been contentious; court decisions and state regulations produce a patchwork of practices. Some states use "use it or lose it" approaches that trigger confirmation notices after a period of inactivity. Others conduct proactive purges based on address mismatches. The result is inconsistency: in one county, someone who hasn't voted in two cycles might get a notice; in another, they remain on the rolls indefinitely.

Political incentives matter too. Research shows that the composition of voter rolls can subtly influence turnout by creating friction for certain groups more likely to move frequently—young people, renters, low-income households, and people of color. Where partisan battles over voting access are intense, decisions about purges can be weaponized, even inadvertently, to favor one party's base. That means purges are not just a bureaucratic nuisance: they can shape representation.

How purges actually work in practice

Common purge triggers include:

- Returned mail: Election officials send a confirmation or notice and remove registrants if mail is returned and no further contact is made.

- Death records: Matching with Social Security or state death indexes removes deceased registrants.

- Change-of-address data: Cross-checks with postal or motor vehicle records can flag voters who appear to have moved.

- Criminal convictions: In some states, felony convictions lead to disenfranchisement, requiring official procedures to restore rights.

But the way these triggers are applied varies. Some places require multiple notices and long waiting periods; others remove names after a single failed match. Some data-matching algorithms are conservative; others are aggressive. Importantly, wrongly purged voters can be restored, but the process to re-register or to cast a provisional ballot varies and can be confusing.

Why this matters for everyday people

At stake is more than a name on a list. Voter registration status affects the ease with which someone participates in democracy. A purged voter who shows up at the polls may face long lines, provisional ballots that are later rejected, or simply the frustration of realizing they aren't eligible. These experiences are discouraging and disproportionately impact communities that already face barriers to participation.

I've interviewed election officials who care deeply about fair rolls and work under chronic constraints—limited budgets, seasonal staff shortages, and political pressure. Balancing the legitimate need to maintain accurate rolls with the imperative to maximize participation is complicated. But tolerating wide variation in rules and opaque administrative practices leaves room for errors that undermine trust in elections.

Concrete steps citizens can take right now

Protecting voting rights in the face of purges is partly about systems and partly about habits. Here's what I've found works, both from reporting and from conversations with voters and administrators:

- Check your registration regularly. Don't wait until election day. Use your state's online lookup tool or the nonpartisan sites such as Vote.org or the Election Assistance Commission's resources to confirm your status.

- Update your address promptly. If you move, even within the same city, update your registration or re-register. Many states allow online updates tied to DMV information.

- Respond to mail from election offices. If you receive a confirmation notice, follow the instructions. Even if the mail was sent in error, responding preserves your status while the office investigates.

- Know your restoration process. If you discover you're purged, find out how to re-register quickly and whether you can vote provisionally the same day. Keep proof of identity and residence handy.

- Use technology wisely. Sign up for reminder services—some civic tech tools (like TurboVote or Ballotpedia alerts) and local election offices offer email or text reminders about registration deadlines and polling locations.

- Document interactions. If you're told at a polling place that you're not registered, ask for written information, the name and contact of the official, and capture the exchange if possible.

What communities and organizations can do

Civic groups, nonprofits, and local newsrooms play crucial roles. Voter education campaigns that focus on registration maintenance—especially targeting students, renters, and communities of color—reduce the number of involuntary purges. Legal clinics and “know your rights” workshops help people understand provisional ballots and restoration processes.

Local journalists can shine light on purge practices and hold election officials accountable—reporters I've worked with have used public records requests to map when and how purges happen, prompting policy changes. Tech platforms can help too: user-friendly state portals, clearer notices, and mobile-friendly registration all lower friction.

Policy fixes that would make a difference

Most reforms fall into two buckets: better data practices and stronger safeguards for voters.

| Problem | Possible Fix |

|---|---|

| No standardized notice process | Require multi-step notifications with long cure periods before removal |

| Poor data matching and false positives | Improve matching algorithms, require human review for ambiguous cases |

| Disparate state rules | Federal guidance or model laws that protect against "use it or lose it" purges |

| Lack of resources for election offices | Increased funding and technical assistance for secure, interoperable systems |

In short: reduce reliance on a single noisy data source, demand transparency about purge criteria, and ensure voters have easy pathways to cure any mistakes. Those fixes require political will, but they're pragmatic and measurable.

When to escalate a problem

If you suspect you or others are being targeted—receiving disproportionate purge notices, or seeing errors concentrated in specific neighborhoods—document patterns and contact civil rights organizations such as the ACLU, the League of Women Voters, or local legal aid. These groups can bring litigation, coordinate responses, and draw public attention. For immediate help at the polls, many states list hotline numbers for election-day issues; keep them handy.

Maintaining an accurate, inclusive voter roll is a shared responsibility. Election administrators must do their part, but so must voters, journalists, community groups, and policymakers. If we treat participation as a durable right rather than a privilege that needs constant reapplication, we'll be closer to a system that both respects accuracy and prioritizes access.